Mixed Metals: Accurate CP Potentials and Interpretation

Introduction

Cathodic protection (CP) strategies have long focused on steel, with well-established criteria like the -850 mV instant off potential versus a copper-copper sulfate electrode (CSE) or 100 mV of polarization. However, modern infrastructure often involves a mix of dissimilar metals. Steel electrically common with copper, stainless steel, aluminum, or other alloys creates a complex electrochemical environment. These mixed metal systems can lead to galvanic corrosion, distorted potential readings, and challenges in verifying protection levels. Misinterpreting these measurements risks accelerated degradation, safety hazards, and costly repairs. As the global cathodic protection market continues to expand, driven by aging infrastructure and stricter regulations, understanding how to accurately measure and interpret potentials in mixed metal scenarios is essential for effective corrosion management. This article explores the principles, techniques, challenges, and best practices for navigating these complexities, equipping technicians with the knowledge to protect diverse metallic assets.

The Fundamentals of Cathodic Protection in Mixed Metal Systems

Cathodic protection operates on electrochemical principles to prevent corrosion by making the protected structure the cathode in an electrochemical cell. For single metal systems, particularly steel, this is straightforward: CP shifts the structure's potential to a level where anodic corrosion is significantly reduced. The standard criterion for steel is a polarized potential of -850 mV CSE, ensuring sufficient current flow to slow or stop corrosion reactions.

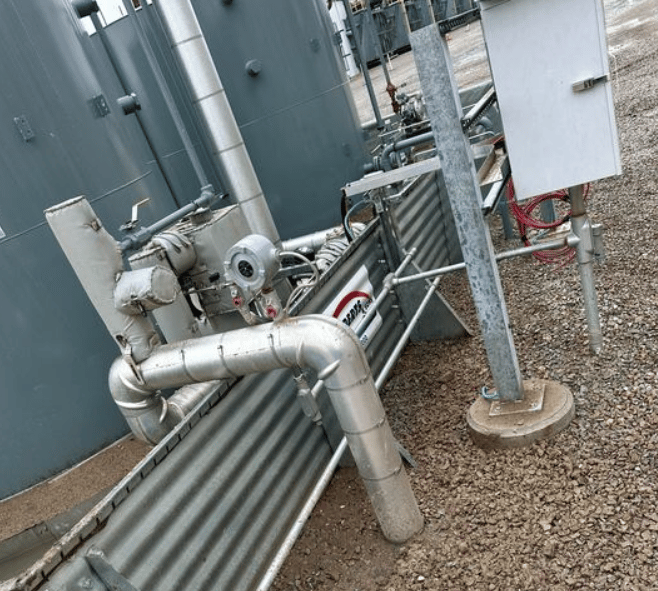

However, when dissimilar metals are present, the dynamics change. Compressor stations with bare copper grounding, shorts to aluminum components, structural supports, communication equipment connections, water lines, etc. Each metal has its own position in the galvanic series, which ranks materials based on their nobility or tendency to corrode. More active (anodic) metals like magnesium or zinc corrode preferentially, while noble (cathodic) metals like copper or stainless steel are protected. In a mixed system, unintended galvanic couples form if metals are electrically connected in an electrolyte, accelerating corrosion on the anodic metal.

In practice, corrosion technicians often encounter these scenarios when surveying pipelines or storage tanks. A steel pipeline running through a facility with extensive copper grounding, for instance, becomes electrically common if there's no isolation. This connection influences not just corrosion rates but also the very measurements used to assess protection. The voltmeter reading doesn't reflect a pure steel potential; instead, it captures a composite value shaped by all connected metals. Understanding this is key to avoiding false assurances of protection.

How Mixed Metals Skew Potential Readings

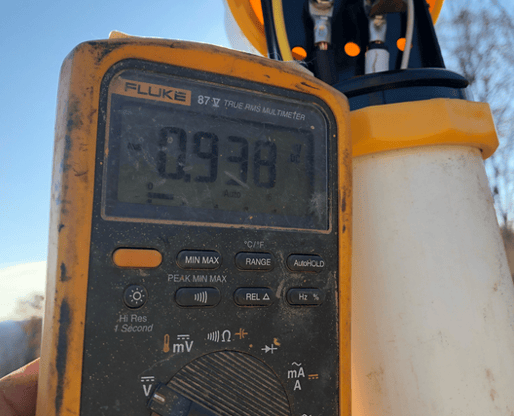

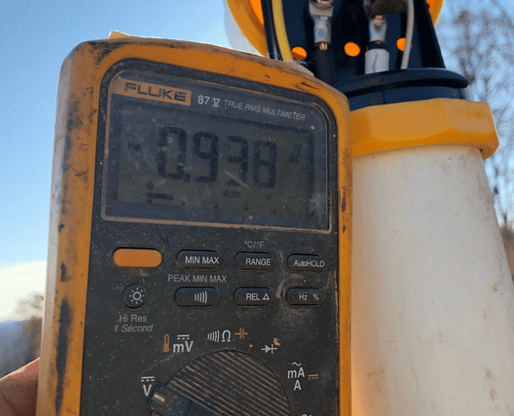

At the heart of the issue in mixed metal scenarios is the way potential measurements are taken and what they truly represent. Pipe-to-soil potentials are measured using a reference electrode, typically a CSE, placed in the soil above the structure. The voltmeter connects the positive lead to the pipeline and the negative to the reference electrode, yielding a reading that indicates the structure's electrochemical state relative to the electrolyte.

In a single-metal steel system, this reading is reliable. Native (unprotected) potentials for steel in soil might range from -500 mV to -700 mV CSE, depending on soil conditions. Applying CP shifts this to more negative values, and criteria like -850 mV instant-off or 100 mV polarization confirm protection.

But introduce copper grounding, and everything changes. Copper has a more noble potential, often around -50 mV to -300 mV CSE in similar environments. When steel and copper are electrically connected, the measured potential at a test point on the steel becomes an average of the two metals' potentials, weighted by their surface areas and the electrolyte's resistivity. Since copper is more noble, it "pulls" the overall reading less negative—perhaps to -500 mV instead of the expected -600 mV for isolated steel.

This skewing affects both depolarized (CP off) and polarized (instant-off) readings. For depolarized measurements, used to establish the native potential for the 100 mV polarization criterion, the reading might show -500 mV when the true steel potential is actually -600 mV. The apparent native potential is artificially less negative due to the copper's influence.

When CP is applied and interrupted for instant-off readings, the skew persists. The instant-off potential, meant to capture the polarized state without IR drop, still reflects the composite of steel and copper. If the system achieves -850 mV instant-off, is it truly protected?

This composite effect is exacerbated in facilities like compressor stations, where bare copper grounding grids are extensive. The large cathodic surface area of copper dominates, making voltmeter readings even less negative. Technicians might calculate a polarization shift of 100 mV based on skewed numbers, assuming compliance with NACE SP0169, only to find ongoing corrosion on the steel.

Challenges in Interpreting Readings for Corrosion Control

Interpreting these skewed readings poses significant challenges for corrosion technicians. NACE standards, such as SP0169 and TM0497, are primarily written for single-metal scenarios, emphasizing criteria like -850 mV polarized or 100 mV polarization for steel. They acknowledge mixed metals but don't always provide detailed guidance on adjusting for composite potentials.

One major pitfall is the false positive in polarization assessments. Suppose a technician measures a depolarized potential of -650 mV (skewed less negative by copper) and an instant-off of -750 mV. The apparent shift is 100 mV, meeting the criterion. However, the true steel native potential might be -720 mV, meaning the actual shift is only 30 mV from the native potential. Corrosion could continue at anodic sites on the steel, hidden by the average reading.

Stray currents add another layer. In mixed metal setups near electrical systems or other CP installations, dynamic stray currents can fluctuate readings, making it hard to distinguish galvanic skew from interference. High-resistivity soils amplify IR drop errors, further complicating interpretations.

Regulatory compliance under frameworks like 49 CFR Part 192 requires documented evidence of protection, but skewed readings can lead to non-compliance if corrosion emerges later. Technicians must recognize when a reading doesn't align with expected values.

Techniques for Accurate Measurements in Mixed Scenarios

To counter these challenges, corrosion technicians need refined measurement techniques tailored to mixed metals.

First, conduct thorough system investigation. Identify all connected metals through electrical continuity tests and visual inspections. Look for the type of grounding used and how it's connected. Determine if other buried metallic structures exist and if they are common.

For potential surveys, employ multiple reference points. Take readings directly over the steel pipeline, away from copper influences if possible, and compare with points near grounding. Check for potential shifts on unintended structures. Consider close-interval potential surveys (CIPS) to map gradients.

External corrosion coupons can be isolated from this effect and used to determine if a CP system is effective. They can provide IR-free, localized potentials less affected by mixed metals.

Adjusting Criteria and Best Practices for Mitigation

Given the limitations of standard criteria, technicians should apply caution in mixed metal interpretations. NACE SP0169 notes that for dissimilar metals, protection must target the most anodic material, but it doesn't specify adjustments for composite readings. A practical approach is to exaggerate polarization targets.

Instead of 100 mV, aim for 200 mV or even 350 mV shift to compensate for skew. For example, if the composite depolarized reading is -500 mV (skewed from true steel -600 mV), target an instant-off of -750 mV or more negative. This ensures the steel achieves adequate protection despite the average.

Electrical isolation is a top best practice. Install dielectric unions, insulating flanges, or monolithic joints to separate steel from copper. There are many options to decouple this connection, but that's an entire topic for another article.

If isolation isn't feasible, boost CP output. Add anodes or increase rectifier current to drive potentials more negative, countering the other metal's influence. Monitor for overprotection, which can cause hydrogen embrittlement in some steels.

Training empowers technicians. Familiarize teams with galvanic series and composite effects through case studies.

Case Studies:

Consider a natural gas pipeline in a compressor station with bare copper grounding. Initial surveys showed depolarized potentials of -420 mV CSE, less negative than expected. Instant-off readings averaged -600 mV, suggesting around 180 mV shift—seemingly adequate but with ongoing pitting on steel. Further investigation revealed a mixed metal skew; isolating sections and aiming for 300 mV shift resolved this.

In another case, a storage tank with different fittings connected to steel showed composite readings of -510 mV depolarized. Technicians used external corrosion coupons to confirm true steel native at -690 mV.

While standards and criteria can guide, mixed metals require some adaptive strategies.

Emerging Trends and Future Considerations

As infrastructure ages, mixed metal challenges grow. Regulations evolve too, with emphasis on risk-based assessments incorporating mixed metal risks. Staying informed through AMPP / NACE updates is the best practice.

Conclusion

Navigating mixed metal potentials requires recognizing that voltmeter readings are composites, not pure indicators of steel alone. Skewed less negative by other metals like copper, these averages can mislead, turning 100 mV polarization into a false security. By mapping systems, using advanced techniques, isolating where possible, and exaggerating targets to 200-350 mV, technicians can help mitigate corrosion effectively. This cautious approach aligns with AMPP / NACE principles while addressing real-world complexities, ensuring asset longevity.

Roberts Corrosion Services, LLC

Established in 2011, Roberts Corrosion Services, LLC delivers comprehensive, turn-key cathodic protection and corrosion control solutions nationwide. Our end-to-end expertise encompasses design and inspection, installation and repair, surveys and remedial work. We provide drilling services for deep anode installations and a full laboratory for analysis of samples and corrosion coupons, as well as custom CP Rectifier manufacturing.

While our initial focus was on the Appalachian Basin area, we complete field work all over the US. We are a licensed contractor in many states and can complete a wide range of services.

Our biggest strength is in our flexibility for our clients. Solutions and Results.

Let us know how we can help.

Website

LinkedIn

Location: 39.251882, -81.047440

(304) 869-4007