How to Complete a Current Requirement Test: A Guide for Corrosion Technicians

Introduction: The Critical Role of Accurate Cathodic Protection in Corrosion Control

In the world of corrosion control, ensuring the longevity and integrity of buried metallic structures like pipelines, storage tanks, and well casings is paramount. These assets form the backbone of industries such as oil and gas, water distribution, and infrastructure, where even minor degradation can lead to leaks, environmental hazards, and costly downtime. Cathodic protection (CP) stands as one of the most effective defenses against this electrochemical enemy, but its success hinges on one key factor: delivering the right amount of protective current.

Determining the precise current requirements for a CP system is not just an estimation. Traditional engineering designs often rely on calculations involving surface area, soil resistivity, and assumed coating efficiency, but these can fall short in capturing real world variables like varying environmental conditions or unforeseen coating defects. This is where the current requirement test (also known as the current response test) comes into play. By applying temporary current and measuring the structure's response, technicians can obtain data that reflects actual conditions, offering a more reliable basis for CP system design than theoretical models alone.

This article serves as a resource for corrosion technicians needing to complete a current requirement test. We will explore the underlying principles, detail the equipment and procedural steps, explain how to interpret results, and discuss best practices to ensure accurate and safe outcomes. Whether you're assessing a new installation or optimizing an existing system, understanding this test allows you to make informed decisions that enhance structure protection and operational reliability.

The Fundamentals: What is a Current Requirement Test and Why Conduct It?

At its core, a current requirement test evaluates how a metallic structure responds to applied direct current (DC), determining the amount needed for adequate cathodic protection. The test simulates a CP system by applying current from a temporary source and monitoring the shift in the structure-to-electrolyte potential. This potential shift indicates the level of polarization, showing how much current yields how much resulting protection.

The test is grounded in electrochemical principles. Corrosion occurs through anodic reactions where metal ions dissolve into the electrolyte, balanced by cathodic reactions that consume electrons. By supplying external current, the CP system forces the entire structure to act as a cathode, suppressing anodic dissolution. The current requirement test measures the minimum current density required to polarize the structure to a protective potential, accounting for factors like bare metal exposure, electrolyte conductivity, and environmental influences.

Why opt for this hands-on approach over paper-based calculations? Engineering estimates often use formulas like the modified Dwight equation for anode output or assumptions about coating efficiency (e.g., 95-98% for well-coated pipelines). However, these can overestimate or underestimate needs due to unaccounted variables (localized soil conditions, unexpected coating holidays, etc.). A field test, by contrast, provides measurable, site-specific data. For instance, theoretical models might predict low current needs, but actual testing could reveal higher demands due to poor current distribution. This real-world validation reduces the risk of under or overprotection, which wastes resources or may cause issues like coating disbondment.

Industry standards, including those from AMPP (formerly NACE) such as SP0169 for pipelines and SP0572 for design criteria, emphasize the value of such tests for CP system commissioning and optimization. Conducting a current requirement test is particularly useful during the design phase of new structures, after coating repairs, or when troubleshooting underperforming CP systems.

Core Principles: The Electrochemical Basis of Current Response

To perform the test effectively, it's essential to understand the electrochemical dynamics at work. When current is applied, it flows from the anode (temporary in this case) through the electrolyte to the structure, polarizing its surface. The potential measurement, taken with a reference electrode, reflects this shift. The goal is to reach a criterion like -850 mV (instant-off) versus CSE or to show a minimum of 100 mV of polarization added.

Key concepts include:

Polarization and Depolarization: Applied current causes a negative shift in potential. Upon interruption, the potential decays, revealing the true polarized state minus IR drop.

Current Density: Expressed in milliamps per square foot (mA/ft²), this measures current per unit of exposed surface area. Typical requirements range from 1-3 mA/ft².

IR Drop Considerations: Measurements may contain significant IR drops, masking true potentials. Tests need to use current interruption to determine the polarized potential.

Environmental Influences: Factors like temperature, pH, oxygen levels, and microbial activity affect current needs. For example, anaerobic soils may require a -950 mV criterion to combat sulfate-reducing bacteria.

The advantage of this test is its hands on approach. Engineering estimates often depend on equations like I = (A × CD) / CE. Where I is total current, A is surface area, CD is current density, and CE is coating efficiency. The field test directly measures response, bypassing assumptions. It's similar to conducting an on-site load test for a bridge instead of depending entirely on design drawings.

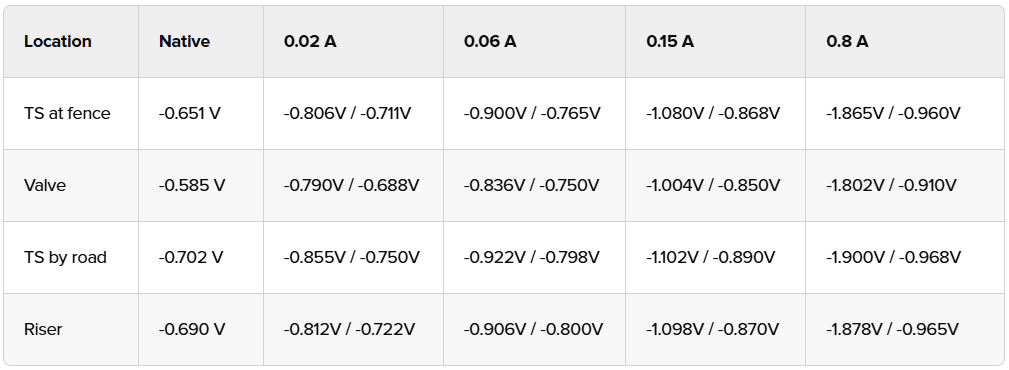

Equipment Essentials: Tools for Accurate Testing

Selecting the right equipment is crucial for reliable results. Here's a breakdown of some standard items:

Temporary DC Power Source: A battery bank, portable rectifier, or something capable of 0.1 - 10 amps output, measurable and adjustable in increments. There are several instruments from different CP vendors built specifically for this type of test.

Digital Multimeter: High-impedance, good test leads, and calibrated. It's useful to have more than one available.

Reference Electrode: Copper-copper sulfate (CSE) cleaned and calibrated. It's useful to have more than one available.

Temporary Anode: Steel rods, galvanic anodes, even other structures to simulate a ground bed. Moist soil for low resistance is helpful.

Cables and Connections: Insulated #10 AWG wires with alligator clips or bolted terminals.

Safety and Utility Tools: Non-contact voltage detector, PPE (gloves, glasses, vest, hard hat), utility locator, shovel, and data logger or notebook.

Optional Advanced Tools: Soil resistivity (e.g., Wenner four-pin method) or GPS for mapping, per company procedures.

Step-by-Step Guide: Performing the Current Requirement Test

While each test is unique, the steps below are a generalized outline.

Preparation Phase

Review the structure's schematics and if there is any existing CP data. Identify test points like test stations or exposed sections.

Gather native data. 'As Found' potentials and any relevant information.

Inspect and calibrate equipment. Verify no live voltages on the structure using the non-contact detector.

Ensure the location is representative of the structure section to be protected (e.g., avoid isolating joints or casings unless testing specific issues).

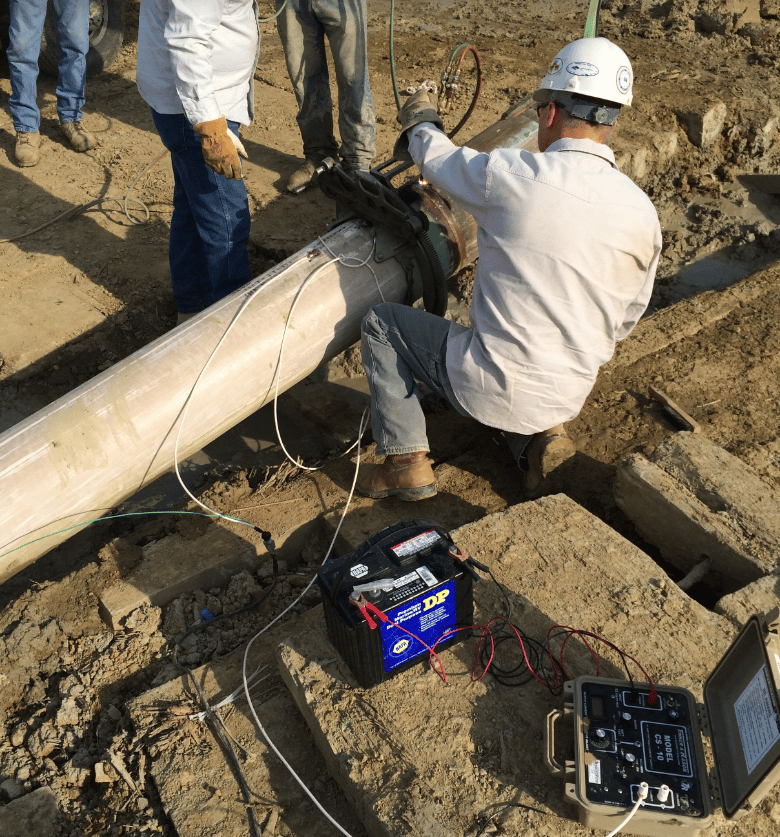

Setup Phase

Select a location for the temporary anode bed with good access, away from anything that might interfere with the output (other large structures, CP systems, etc.).

Install the temporary anode bed away from the structure being tested and in moist soil. Depending on the size of the structure, this may need to be 50 - 100ft away. Moisten the soil or water around the anode to improve conductivity. Multiple anodes can be used to reduce resistance.

Setup the circuit: Positive lead from power source to anode, negative to structure. Insert a shunt in series for measuring a mV drop to calculate current (or use an ammeter). Have everything laid out, but do no make the final connection until after the native potentials have been recorded.

Testing Phase

Measure the native (baseline) potentials: Place the CSE at the selected test points and record the structure-to-electrolyte voltages (typically -500 to -700 mV for unprotected steel).

Apply incremental current: Starting at the lowest output, gradually increase the current while monitoring potentials. Allow at least a minute or two for stabilization. Aim for a measurable increase in current and polarization voltage (e.g., 20mA output for 150mV increase in potentials).

Interrupt current briefly (instant-off) at each increment to also measure polarized potential, eliminating IR drop.

Continue increasing the output and recording the data at reasonable and incremental steps.

Continue until the potential reaches or exceeds the protection criterion (e.g., -850 mV instant off). Note the minimum current achieving this.

If testing multiple points, repeat along the structure to assess uniformity.

Post-Test Phase

Disconnect and remove equipment, restoring the site.

Document all readings, including date, time, weather, and anomalies.

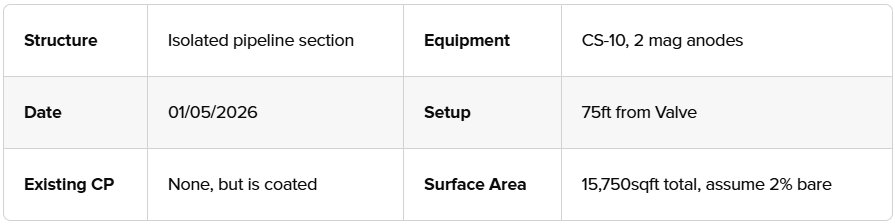

An example test sheet may look like:

Interpreting the Results: What the Data Reveals

The raw data (current applied versus potential shift) provides insights into protection needs. Plot potential (y-axis) against current (x-axis) for a linear or semi-linear curve. The slope indicates resistance; a steeper slope means higher efficiency (less current needed).

Minimum Current Requirement: The lowest amperage yielding -850 mV instant off at the lowest test point measurement.

Current Density Calculation: Divide current by estimated exposed area (e.g., if 0.15 amps protects 315 ft², density is 0.5 mA/ft²—indicating good coating).

Possible Anomaly Indicators: A minimal shift could suggest an electrical short or high-resistance contact to something unintended. Fluctuations point to interference; address by investigating, adjusting, and retesting.

Results mean the difference between effective CP and estimated guesses. Higher than expected requirements (>5 mA/ft²) warrant further surveys like CIS or DCVG to identify issues.

Conclusion: Empowering Technicians for Superior Corrosion Control

The current requirement test combines theory and practice, providing the empirical data for effective cathodic protection systems. By using this method, corrosion technicians can ensure structures receive precisely the current needed, extending asset life and minimizing risks. As industries evolve with tighter regulations and advanced materials, this test remains a cornerstone of proactive maintenance. Regular application not only complies with standards but positions teams to anticipate and prevent corrosion challenges effectively.

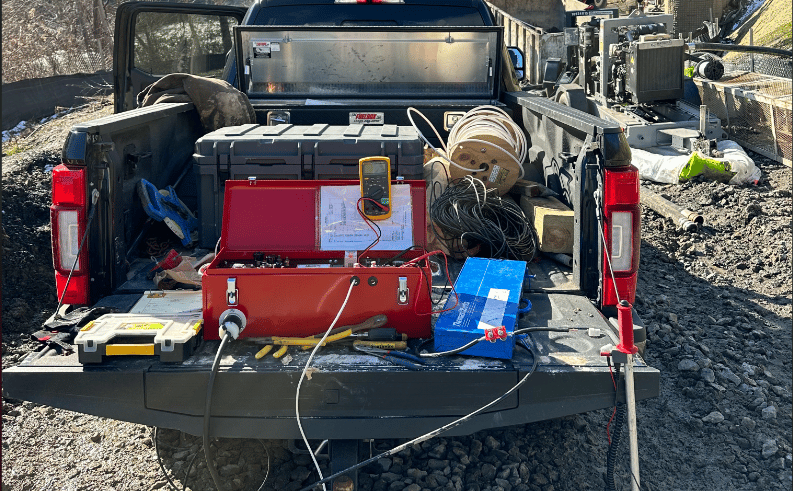

Roberts Corrosion Services, LLC

Established in 2011, Roberts Corrosion Services, LLC delivers comprehensive, turn-key cathodic protection and corrosion control solutions nationwide. Our end-to-end expertise encompasses design and inspection, installation and repair, surveys and remedial work. We provide drilling services for deep anode installations and a full laboratory for analysis of samples and corrosion coupons, as well as custom CP Rectifier manufacturing.

While our initial focus was on the Appalachian Basin area, we complete field work all over the US. We are a licensed contractor in many states and can complete a wide range of services.

Our biggest strength is in our flexibility for our clients. Solutions and Results.

Let us know how we can help.

Website

LinkedIn

Location: 39.251882, -81.047440

(304) 869-4007